Color Transparency

“Color transparency” refers to the vanishing of initial and final state interactions in exclusive processes at large momentum transfer. My dissertation experiment took data in early 2018 to study the onset of color transparency in quasielastic scattering off a carbon-12 target. That’s a lot of jargon, so let’s take a step back.

Historical uses of particle beams to study nuclear structure

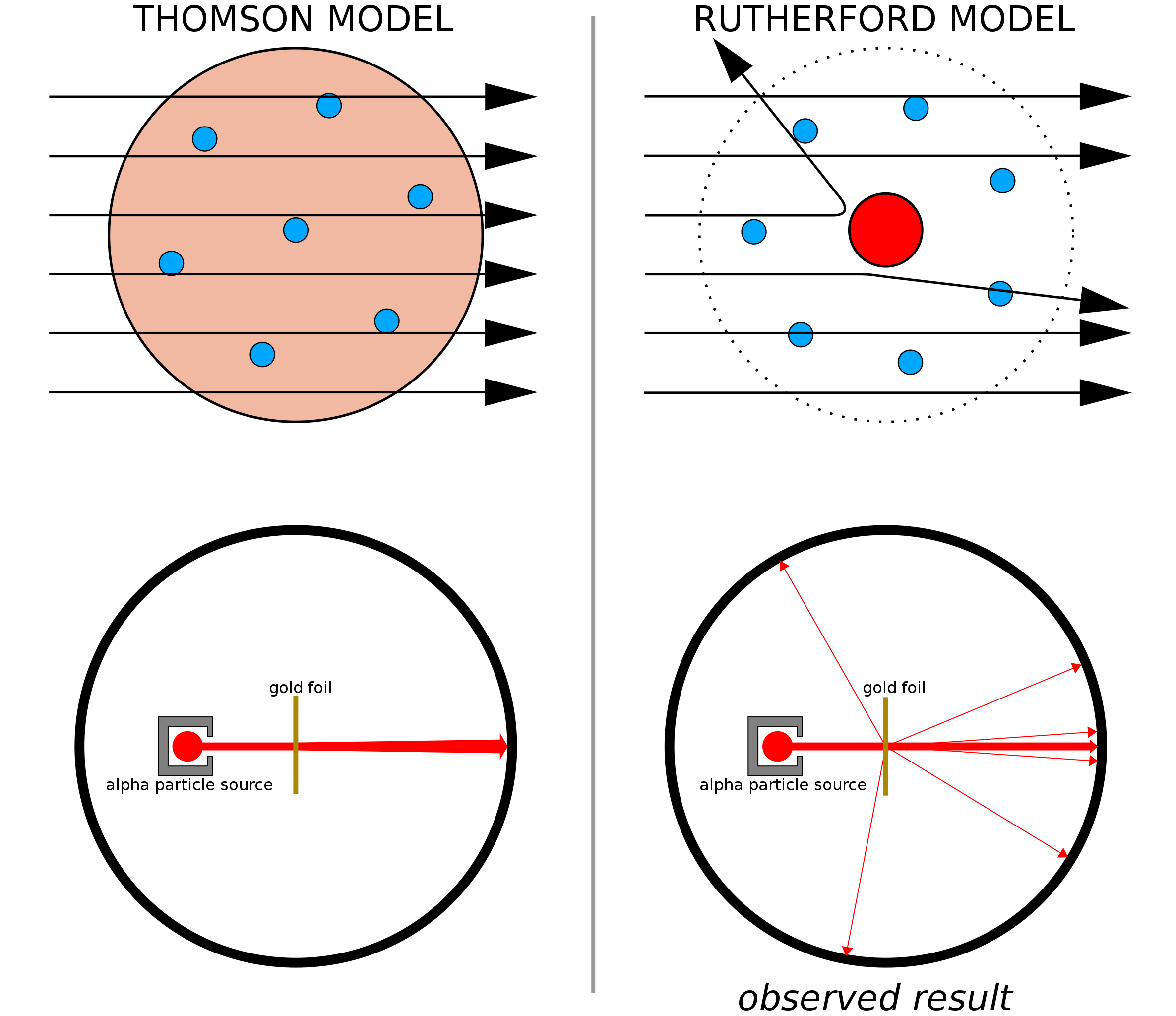

Around 1910, Rutherford, Geiger, and Marsden used a beam of alpha particles incident on a gold foil to study atomic structure. Their results suggested that the atom is composed of a small, dense, positively charged nucleus surrounded by a cloud of electrons. This result contradicted the predictions of Thomson’s plum pudding model, which held that the atom was a uniform sphere of positive charge with electrons scattered around its interior, like bits of fruit in a British Christmas pudding.

In the century since, physicists have used other particle beams to study the substructure of nuclei as well as the nucleons (i.e. protons and neutrons) that compose nuclei. The culmuniation of decades of such experiments is a theory called quantum chromodynamics (QCD): the theory that quarks and gluons are the fundamental building blocks that make up hadrons, a category of composite particles that includes protons and neutrons.

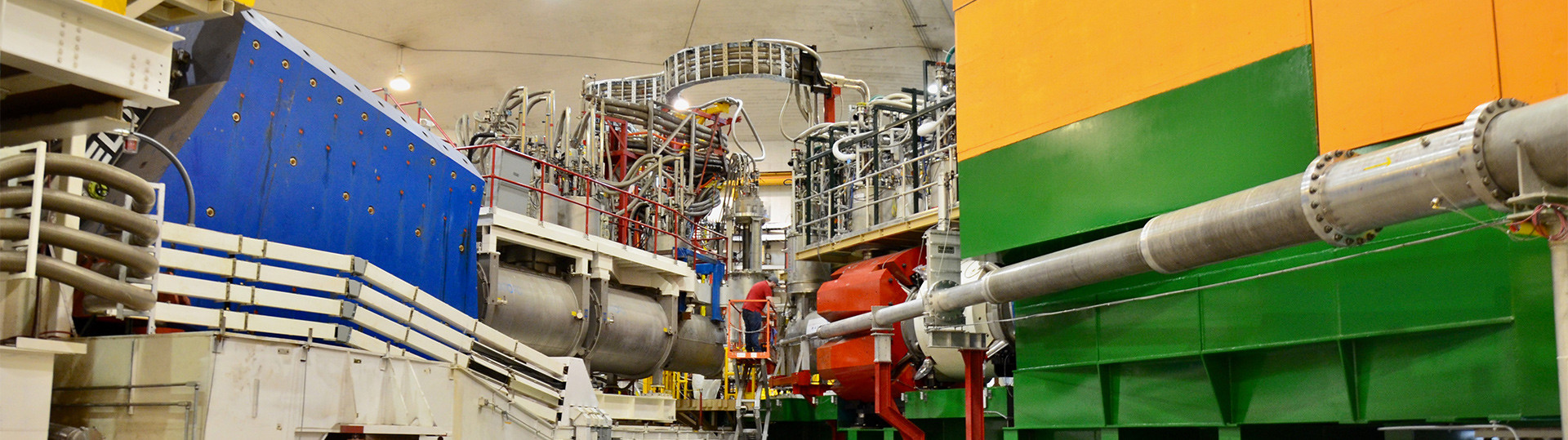

The Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility (JLab) in Newport News, VA is home to the Continuous Electron Beam Accelerator Facility (CEBAF). The CEBAF beam delivers a 12 GeV beam of polarized electrons to four experimental halls. Most JLab experiments study the debris produced when the CEBAF electron beam hits a fixed nuclear target. By studying the debris, physicists are able to obtain new insights into nuclear and nucleon structure, exotic configurations of quarks, and other facets of QCD.

Scattering in classical physics

Now what exactly is “quasielastic scattering”? Elastic scattering is something you might be familiar with from introductory physics courses. In Newtonian physics, an elastic collision is one in which kinetic energy is conserved. A canonical example is an air hockey puck hitting another puck on a frictionless plane. An inelastic collision is one in which kinetic energy is not conserved. A canonical example is two wads of gum colliding and sticking together in zero gravity.

Scattering in nuclear physics

In nuclear physics, the canonical example of elastic collisions is an electron colliding with a free proton. The collision is elastic in the sense that the incoming and outgoing particles all retain their “identities.”

One of the fun aspects of quantum field theory comes from the intersection of quantum mechanics and relativity. Energy and matter are in some sense interchangeable, so some of the energy contained in colliding particles can be converted into mass. This is how collisions of proton beams at the LHC create short-lived particles like the Higgs boson.

At “low” energies, an electron colliding with a nucleus will kick out a proton or neutron. Physicists can use this process to study how tightly bound individual nucleons are in a particular nucleus.

At higher energies, some of this E=mc^2 energy can be converted into “new” particles! Instead of nucleons, particles like pions and kaons come out of the collision. At this energy scale, we start probing sub-nucleon structures instead of nuclear structures. Physicsts call these types of interactions “deep inelastic scattering” because we are using scattering processes to study the “deep” structure of strongly interacting matter.

Quasielastic scattering is the “low” energy process where the collision looks like the elastic case of an electron colliding with a free proton. None of the energy is converted into “new” particles. The electron transfers momentum to one of a nucleus’s constituent proton, removing it from its bound state in the nucleus. This interaction is called “quasielastic” because it looks more like an electron hitting a free proton than it does a deep inelastic interaction.

Multiple scattering theory

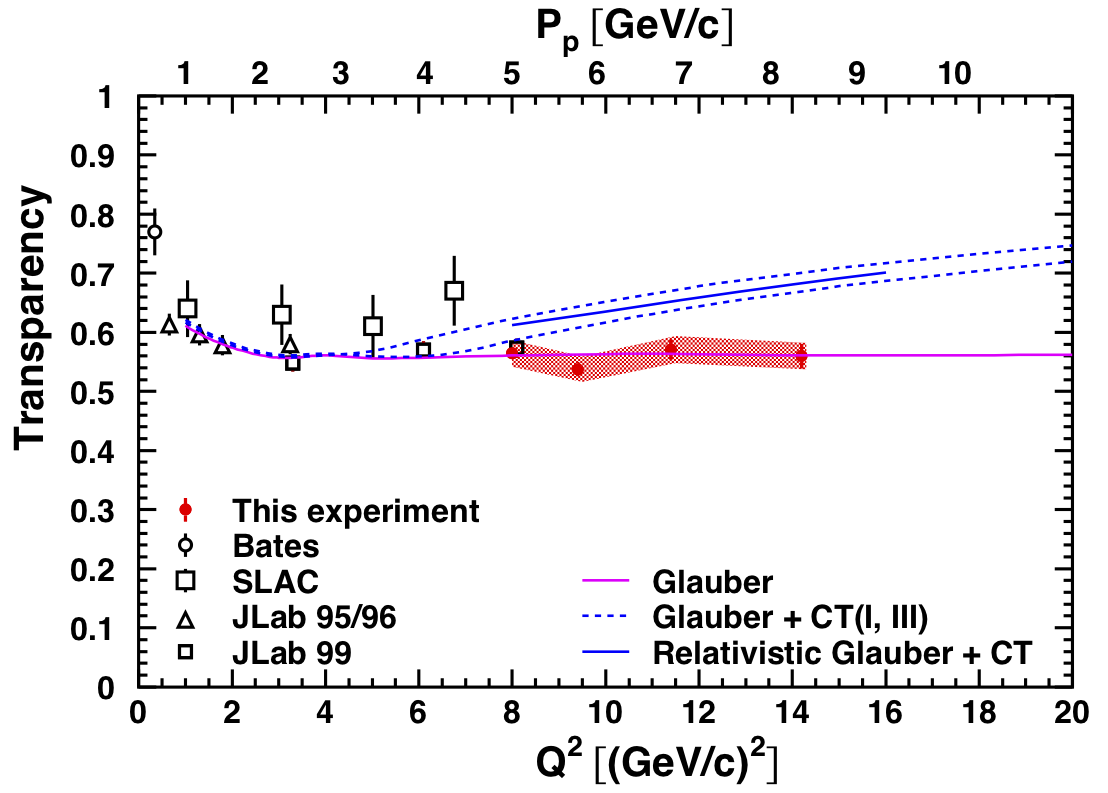

You might imagine that when a proton is knocked out of a nucleus, it bumps into the other protons and neutrons on its way out, and this is typically what happens! The theoretical framework for modeling these bumps is called Glauber multiple scattering theory. It’s a model that works remarkably well and has been used, with some tweaks depending on context, in experiments at facilities like JLab and the LHC. One of the predictions of the Glauber model is that the probability for an ejected proton to escape without bumping into another nucleon should be relatively constant as the amount of momentum transferred from a beam electron to the proton increases. The quantity we measure in an experiment that corresponds to this probability is called nuclear transparency, typically denoted by the letter T.

Color Transparency

Now here’s where things get weird. In 1982, the theorists Alfred Mueller and Stanley Brodsky both predicted that in particular contexts (exclusive scattering processes at large squared four-momentum transfer), interactions like those between the ejected proton and the rest of the nucleus in quasielastic scattering will disappear. The proton actually shrinks to a very small size and squeaks through without bumping into anything! The conditions for this to occur are:

- Squeezing - the proton shrinks to a small size at large momentum transfer

- Freezing - it maintains this small size for a distance comparable to the radius of the nucleus

- Vanishing interactions - the strength of nuclear interactions decrease with increasing momentum transfer

If these conditions are met, the nuclear transparency T should rise with momentum transfer. Theorists have developed models (e.g. Frankfurt et al. and Cosyn et al. ) that expand the Glauber approach to include these necessary conditions. The only open question with these models is exactly how high an experiment needs to push momentum transfer in order to “turn on” this effect. How much momentum does the electron need to pump into a proton in order to squish it down and make it squeak out of the nucleus without rescattering?

This is the central question my dissertation experiment explored. Previous experiments had studied a range of momentum transfer up to 8.0 GeV^2. My experiment took advantage of the recent upgrade to the CEBAF accelerator at JLAb to extend this range up to 14.2 GeV^2.

Our results

We took data in JLab’s Hall C, shown below, home to two large apparatuses that collect and analyze the debris generated in collisions between the electron beam and nuclear targets. The High Momentum Spectrometer (HMS; left) and Super High Momentum Spectrometer (SHMS; right) each consist of a set of magnets and detector systems that were designed and built by collaborators around the world.

For my experiment, we set up the SHMS to collect protons knocked out of the nucleus and the HMS to operate in coincidence, collecting the corresponding electrons that knocked the protons out. The results of our measurements (below) do not show a rise in transparency. They’re consistent with the prediction of the traditional Glauber multiple scattering model. If color transparency exists in this scattering process, it apparently doesn’t “turn on” until an energy scale above what we are currently able to study at JLab.

If you’d like to read about color transparency in more detail, these papers are a great place to start.

- Color Transparency Phenomenon and Nuclear Physics by Frankfurt, Miller, and Strikman

- Color Transparency: past, present and future by Dutta, Hafidi, and Strikman